Rural America, Regenerative Ag, and Giving a Damn

- Neva Roenne

- Aug 13, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 26

I picked up A Bold Return to Giving a Damn hoping it would help me understand the agriculture and food systems in a way I couldn't in the classroom. What I got was a raw and reflective look into what it means to care about land, about people, the food system, and about the future of rural America. It left me nodding, challenged, convicted, and a little fired up.

This isn’t a book review. It’s a reflection. A conversation starter. A call to think bigger about what it really takes to grow food and community in a world that often forgets about both.

White Oak Pastures

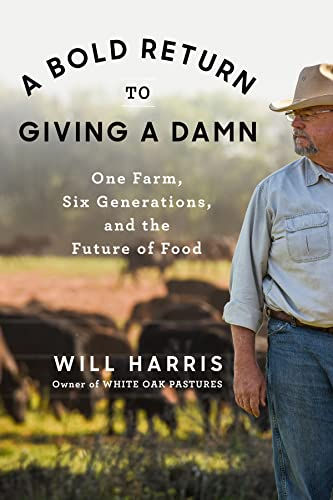

A Bold Return to Giving a Damn: One Farm, Six Generations, and the Future of Food tells the story of Will Harris, a fourth-generation cattleman from Bluffton, Georgia, who traded in industrial farming methods for a regenerative approach that puts the land, the animals, and the community first.

Harris grew up in the heart of conventional agriculture, where efficiency and volume ruled. Over time, he saw the cost — soil stripped of life, animals treated as commodities, and rural communities left behind. The book walks through his decision to break from that system and return to a style of farming that works with natural cycles.

Today, White Oak Pastures is an ecosystem of multiple animal species, on-site processing, composting, and local jobs. It is not a flawless blueprint but a living example of what it looks like to rebuild trust between people and the land.

This isn’t just a book about cattle or compost. It is about what happens when a community refuses to give up on itself.

At its heart, the book is about more than farming. It is about the courage to question the way things have always been done and the persistence to build something better.

What It Gets Right

There were parts of this book that felt like someone had finally said out loud what so many rural folks feel deep in their bones. It talked about how hard it is to watch small towns hollow out. How generational farms get swallowed by corporations. How it feels to give your life to a piece of land and still struggle to make ends meet.

One of the book’s greatest strengths is its refusal to romanticize farming. Harris is clear-eyed about the challenges, but he’s also deeply specific about what’s broken and what can be fixed.

He paints a vivid picture of rural decline like empty storefronts on Bluffton’s main street, school enrollments shrinking year after year, and neighbors forced off their land when industrial agriculture made it impossible to compete. This isn’t just an economic shift; it’s a slow unraveling of community.

Harris also nails the hidden costs of industrial farming for the farmers themselves. He describes debt cycles fueled by expensive equipment, fertilizer, and feed. Farmers in that system, he explains, are reduced to price-takers, selling into a market where they have no leverage and little hope of earning enough to pass the farm to the next generation.

Where the book shines brightest is in showing that regenerative agriculture is about more than healthier soil. It’s about rebuilding the social and economic fabric of small towns. At White Oak Pastures, rotational grazing, multi-species integration, and cover cropping have brought the land back to life, but they’ve also brought jobs back to Bluffton. Harris explains how having their own processing plants keeps more value in the local economy, how improved soil health reduces dependence on outside inputs, and how better animal welfare aligns with better business.

I learned so much about big ag, big food, and big pharma. Don't get me wrong, I'll be the very first to admit that we need big ag to feed the world and have a voice for farmers (especially politically). However, this book brought things to my attention:

The cycle of ultra-processed foods leading the health issues which keeps big-pharma in business.

Brazilian beef is shipped to the U.S., labeled as a product of the USA in the ports, then sold as American beef when the animal never stepped a hoof on US soil; Imported beef often comes from land that was cleared from tropical rainforest, but because the production happens overseas, the environmental damage isn’t counted against U.S. agriculture’s footprint.

USDA regulations favor massive centralized slaughterhouses over small, local processors, making it harder for regenerative farms to compete even when demand exists.

These are just a few examples. I'm not sure if those upset you, they definitely upset me. Mr. Harris is trying to do his part to fix it though. And I admire that.

Just because this is how the system works, that doesn't mean it has to.

Harris is quick to point out that none of what he has done is a fairy tale. Regenerative farming is labor-intensive, margins are still slim, and every day brings a new set of challenges. But because he refuses to oversimplify it, the victories feel earned which is proof that you can feed people, sustain land, and revive a town if you’re willing to fight for it.

Where It Challenges Me

I didn’t agree with everything in the book, and I think that’s part of why I liked it. It wasn’t trying to be easy or neat. Some of the ideas around regenerative agriculture, capitalism, and scaling made me pause. Because while the vision is beautiful, the reality is complicated.

Harris talks about closing the loop, raising animals, composting waste, and rebuilding soil in a way that is poetic and proven at White Oak Pastures. But it also made me think about the farms that operate on razor-thin margins, already strapped with debt, with no spare capital for new fencing, pasture rotation, or on-farm processing facilities. It is not just a matter of doing the right thing. It is about whether they can keep the lights on while they try.

Not every farm can be White Oak Pastures. Not every family has the financial cushion to take a five-year profit hit while they transition land. Many farms' biggest obstacle is simply trying to operate in drought, which isn't the case in Bluffton, GA. Not every community has the infrastructure, local processors, skilled labor, and distribution networks to build a regional food system from scratch.

What challenged me most was realizing that even if the demand for regenerative food grew overnight, the system is not built to let small farms scale without sacrificing their values (those values tend to be a farmer's most precious thing). The bottlenecks in processing, the control of supply chains by a few corporations, and the gap between consumer willingness to pay and the actual cost of production are all real obstacles.

But here is the thing: That does not mean we stop trying. It means we tell the truth while we do it. We name the barriers. We ask better questions. We get more creative about solutions. And we stay at the table even when it is uncomfortable, because the alternative is walking away, and that is not an option.

The Conversations We Need

This book reminded me that agriculture is never just about food. It’s about people. If we want a food system that’s truly sustainable, we have to be willing to have harder conversations. The kind that don’t fit on a bumper sticker.

Like:

Who owns the land, and who gets left out?

What happens to rural kids with no reason to stay?

How to support small farms beyond "shop local" slogans?

How policy, money, and power shape everything, and who that helps or harms?

These aren’t easy topics. But avoiding them doesn’t help anyone. Least of all the people still showing up every day to raise cattle, grow vegetables, and keep the lights on in communities most people only fly over.

Food = People

We can’t talk about food without talking about people.

Not just the chefs or influencers or brands, but the people on the ground. The ones who feed animals and fix tractors and show up to the co-op meetings. The ones who still believe that land and legacy mean something.

A Bold Return to Giving a Damn doesn’t have all the answers. But it reminded me that giving a damn is where it starts.

“We can’t regenerate the land if we don’t also regenerate the systems and the people it supports.”

That’s the line I keep coming back to.

This book challenged me to think about what I’m building and who it is for. To look harder at the systems I’m part of. To remember that the most important thing I can do is care—and act like I do.

Because rural communities don’t need pity. They need partners. They need investment. They need people who still believe it’s worth fighting for something different.

People who give a damn.

All my love,

Neva

Comments